5Rights reactions to Ofcom's 'Making Sense of Media' research

Last week, Ofcom published their annual media literacy research for children and young people called ‘Making Sense of Media’. We have picked out four areas of interest that stood out.

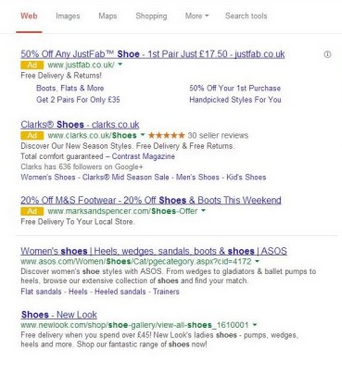

1. Children and young people’s ability to distinguish commercial advertising on Google search results hadn’t changed since 2015.

Google dominates the Search market: handling 93% of all search queries worldwide, and processing 3.5 billion searches every day. Yet only 24% of 8-15-year-olds correctly identified that results which appeared at the top of Google search page had paid to be there.

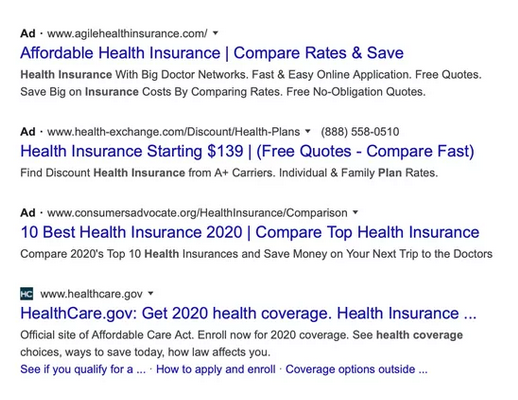

Since 2007, the way that Google indicates paid-for content in Search results has become less and less clear. In 2007, it placed adverts in a coloured box, separate from other search results. In 2013, it removed the coloured box, and added a yellow AD underneath the title, which became a green AD in 2016.

Today, organic search results are formatted to resemble ads (see below).

Alex Hern from the Guardian, said “I would argue there is now no visual distinction between ads and results.” Natasha Lomas from TechCrunch, called it “Google’s latest user-hostile design change”, and Jon Porter from the Verge, added that it “appears to be something of a purposeful dark pattern.”

Early data suggests that Google’s changes are causing more people to click on paid-for content, increasing from a 4.5% to a 10% click-through rate. This a significant increase. If 3.5 billion searches are made each day, that means that 192 million extra ads are clicked.

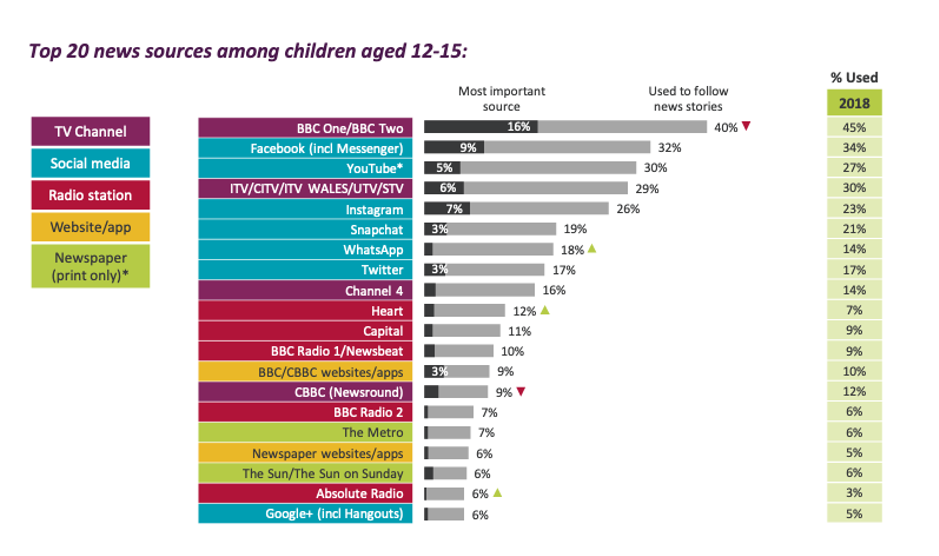

2. Social media sites are six of the top eight news sources for children aged 12-15, despite young people saying that news via social media is the least trustworthy.

As concerns about misinformation campaigns – appearing as news, and spread virally via social media channels - plagues countries, governments, and civil society organisations worldwide, Ofcom has found that social media sites are six of the top eight ways for young people to receive news. 27% of 12-15-year-olds cited social media as their most important source of news, almost double that of BBC One or Two. It says:

“social media is seen as the least trustworthy source of news, but this doesn’t seem to affect its importance to children. Almost three-quarters say online is an important source of news to them – ahead of radio, although radio is considered to be twice as trustworthy.”

There are broader concerns about children and young people’s engagement with the news:

- The nature of unregulated online platforms increases the likelihood of disinformation and misinformation. Angie Pitts, Director of NewsWise, says “young people are sourcing news on platforms that aren’t curated, where it can be difficult to identify sources and where disinformation is rife… it is easy to exist in filter bubbles, and where debate can be unbalanced, non-factual and aggressive.”

- Character limits and video mediums reduce the accuracy and importance of news events. Young people increasingly using memesto consume news on platforms like TikTok which some say cannot accurately convey the nuances of complex events.

- Young people as an audience are ‘tuning out’ due to violent and ‘depressing’ news. Recent research by Reuters Institute Digital News found that anxiety around news in the digital environment affects younger audiences, who are “tuning out.” Ofcom noted that young people are seeking instead, news on subjects like sport, entertainment and celebrities, or about their favourite bloggers.

3. The likelihood of children and young people having seen hateful content online is increasing, although only a minority choose to take action against it.

In 2019, half of 12-15s had seen something hateful online, yet despite a relatively high awareness of reporting functions online (two-thirds were aware of reporting functions on sites, apps and games), there was not a similar increase in the number choosing to take action against it. In fact, 58% of young people chose to do nothing and ignore it. 16% blocked the person who shared it or commented, and 14% reported it to the website. Some young people had shared the harmful content with friends in order to say it was wrong or to comment on it – inadvertently giving content greater exposure.

Some of the stories reported by the Media Lives project:

“Some kids were beating up another child and then nearly shoving a wooden stick with nails in it down his throat.”

“You see a lot of fight videos. A lot of stabbings that people record.”

“Self-harm content on Snapchat goes around the whole school. It’s a common thing…”

Consumer and child advocates are concerned that despite promises to police inappropriate content, many platforms continue to show violent imagery, drug references, racist language and sexually suggestive content that reaches children. If children and young people are increasingly exposed to harmful content online, there is a concern that this type of content is normalised and will become an ordinary part of being online.

But why so few reports from children and young people? This reflects a wider finding that children and young people often appear disinclined to report harmful content. Ofcom’s Media Lives research said:

“Many of the children had seen content that might need to be reported, such as explicit photos or examples of hate speech, but most had not reported it. The report button was not seen as an effective way of policing online content and the children felt it was more effective to reply to the message themselves or ignore it. Few respondents felt that clicking the report button would be an effective way of preventing online abuse, and some clicked it to report friends as a joke.”

Instead of reporting content, Ofcom found that children took alternative ‘reporting strategies’ including telling a parent, and seeking more information about what they had seen. These echoes the findings of Professor Sonia Livingstone OBE’s EU Kids Online research (2020), which indicates that parents, friends and children themselves are overwhelmingly bearing the burden of harmful content online (rather than the platforms they are using). Some of the children in Professor Livingstone’s research “even felt guilty about what had happened.”

4. Young people feel pressure to look good and be popular on social media, sometimes engaging in riskier behaviour to provoke attention online.

Ofcom found that 40% of 12-15s feel pressure to be popular on sites all or most of the time.

“The effects of social pressure were evident… children in the study are becoming increasingly wary about the content they post. Many are so keen that nothing should detract from their online ‘image’ that they keep their profiles virtually empty by deleting old pictures, or those that don’t have enough ‘likes.’”

While some minimised the reach of their online profiles, others used strategies to provoke attention, including posting ‘polls’ and ‘countdowns’ to invite comment from other users, sharing sexualised content, or engaging in ‘shout-outs for shout-outs’ to increase their number of friends and followers.

Ofcom also noted an increase in the use of filtering apps, particularly those which altered and optimised their facial and physical appearance.

A survey by YMCA last year found that 52% of young people felt pressure to look ‘perfect’ by others on social media. Young people don’t just compare their appearance to others’ online. The Prince’s Trust, a charity that helps 11-30-year olds into education, training and work, surveyed young people, of whom half said social media made them feel “inadequate”. 57% thought that social media created “overwhelming pressure” to succeed.

Ofcom’s findings come at a time when policymakers in the UK and abroad are considering regulation to protect young people from online harms. We hope that the experiences of children and young people in the digital environment will play in a central role in these discussions.